The Indus Turned Crimson

On Gendered Violence and Abandoning the Prophetic Example in Pakistan

“The best of you are those who are best to their women.” — Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

What does it mean to march through the streets and chant the name of a man known as 'mercy to all mankind’ — only to then betray everything he stood for with bloodied hands?

For what sin was she killed? The question once buried with infant girls now echoes across the land, where the Indus runs not with life, but with the crimson flow of truth’s lost lungs. It has resurrected itself as the ugly ghost of jahalat, haunting women and girls alike, whose only crime is living, speaking, refusing, dreaming.

The recent tragic discovery of actress Humaira Asghar’s body in her apartment in Karachi has shed light, once more, on the horrific nature of women’s existence in modern Pakistan. Forensic examinations revealed the true tragedy: she had been deceased for at least 8 months before being discovered. Why? Because she committed the crime of being a woman with agency, which, for many in Pakistan, is unforgivable. In following her dreams, she was abandoned, erased, and left to die, invisible and alone.

Last month, 28-year-old Sania Bibi was doused with petrol and set on fire by her husband and father-in-law. Tragically, she succumbed to her wounds a few days ago, after having bravely come forward to share her story and file a report against them. Also in June, seventeen-year-old Sana Yousaf was shot dead in her home in Islamabad after her 22-year-old stalker, Umar Hayat, was enraged when she rejected his marriage proposal. In April, also in Islamabad, university student Eman Afroze was murdered in her hostel, with her killer still roaming free, despite available CCTV footage. While more details about Eman’s case are unknown, each of these tragedies nevertheless reveals a tired truth: far too many men in this country, when met with a woman’s will, turn to the cruel unleashing of violence, whether via the cold mouth of a gun or the heat of fire. Without fear, without hesitation. In these moments of asserting their basic right to breathe, women’s mere existence became their death sentence.

All of these beautiful women’s deaths are a tragedy. What makes them ache more deeply is the all-too-familiar devastation resurrected in each case: witnessing the resurfaced rituals of conversations that fall into the same tired echoes of misogyny we have adopted as the norm. Soon after news of Sana’s murder hit the screens, so too did a barrage of victim-blaming comments desecrating her memory. In a country operating on opposites, where there was only light to be seen, far too many instead saw something to be extinguished.

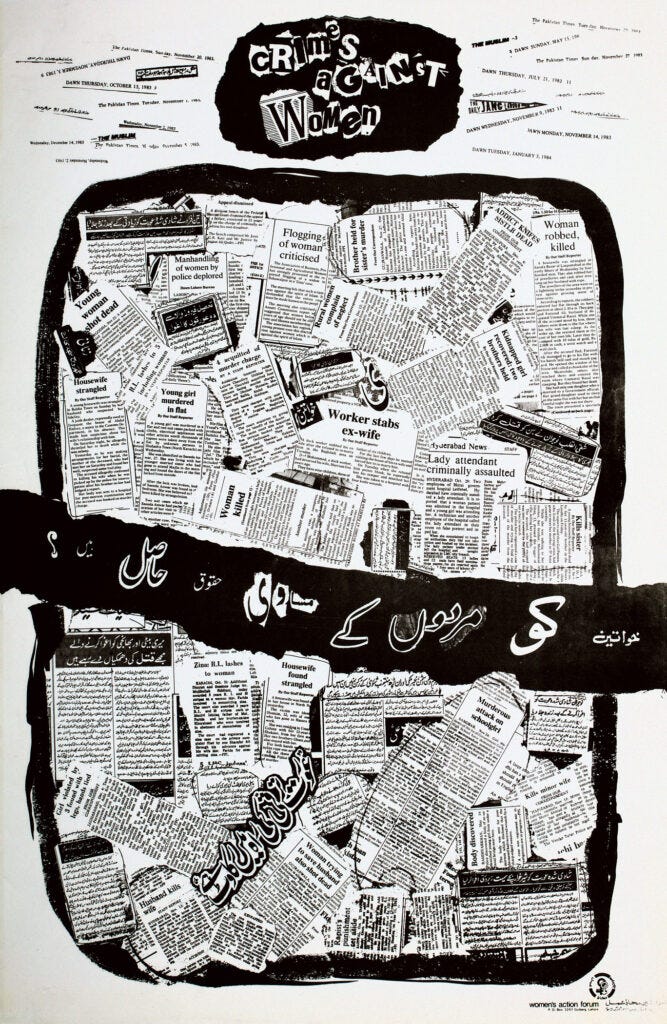

Pakistan’s familiarity with gender-based violence, and in particular its masking in the disguise of religion, is nothing new. Time and time again, we bear witness to the most horrific acts of violence being perpetrated against women and girls, only one percent of which make it to the news cycle. When they do, like clockwork, the language of victim-blaming and shaming arises, perpetuating an age-old narrative that somehow, women are always to blame for the brutality they face. Even when subtly done through remarks feigned with concern about women living alone or daring to work, as was the case with Humaira, the ignorance is no different, and justifies the same terror. For domestic violence victims like Sania, this is an epidemic harder to come up with excuses for — but it is so common that the silence we continue to allow is its very perpetuation.

Social media is a particularly abhorrent place, revealing the ugly face of extremism that exists amongst too many. Following the news of Humaira’s death, some expressed not despair over her circumstances, but anger at her for having chosen to live alone. In Sana’s case, instead of mourning the loss of a child as any sensible human would, men on social media celebrated the murder of a young girl they knew nothing about — all because she dared to have the same thing they do: a social media presence. In a morally bankrupt society and system, the innocent, playful TikTok videos this child made came to define her not as the innocent soul she was, but as an unacceptable reality worthy of such injustice. Humaira’s status as an actress is what warranted her family’s ‘disowning’ of her, and even more sickeningly, their refusal to accept her body. The reactions are reminiscent of Qandeel Baloch’s case, another young woman vilified for asserting agency online — and murdered for it, too. Whether claiming a woman has dishonored her family or dishonored a man’s supposed right to her, their murders are justified. This is unsurprising in a country that finally saw Zahir Jaffer face the consequences of his actions four years later, and still only to have a judge sitting on the bench of the highest court of the land continue to slander and blame his victim, Noor Mukaddam, for her rape and murder. It seems that existing in this society as a woman is an unforgivable sin. No matter your age or class, you will remain an eternal suspect; even in your complete innocence, you are guilty of the crime of owning the body you do. When women and girls are deemed mere property, rejecting a marriage proposal or an unwanted advance can be, and in too many cases is, a death sentence. Her ‘honor’ is questioned and abused not by the actions of her hands but the movement of her lips, uttering the forbidden No.

Victim blaming, unfortunately, doesn’t live in the gutters of social media alone. It is born from its very comfortable thriving in parliament, in the courts, and in our pulpits. This same ignorance plagues the highest and most revered men of this country, and thus it becomes institutionalized — it becomes law, policy, and, consequently, the system we bear the brunt of. Before we know it, it’s radical for a man in power to defend a woman objectively wronged. When the Islamabad Inspector General remarked after Sana’s death that we should encourage young women to do what makes them happy, it came as a welcome shock to many. It is so rare to hear men in such positions speak in a tone not accusatory that even the most basic statements are considered revolutionary. Needless to say, this is a welcome change, because each voice that dares challenge the dominant narrative is a necessary one, one that makes it easier for women and girls tomorrow.

The greatest travesty of this all will forever be the paradox this country lives on. In a country obsessed with women's ‘honor,’ let us ask — where is the honor in this system? Men take to the streets to declare their love for the Prophet ﷺ, who was so steadfast in his compassion towards women that on his deathbed, he still took time to remind men: ‘take care of women’. Where is the honor in their defiance of this instruction — in their ignorance, in their stripping women of life and light?

The religious illiteracy that plagues every rung of society, from bottom to top, is unmistakable, warranting a longer conversation on its impact. It bears the blood of victims far and wide: religious minorities, laborers, women, and girls alike. It reduces Islam, a religion of divine mercy and human dignity, to the personal insecurities of insecure men. The most basic study of Islam will lay out clearly how honor-based violence has no textual or Prophetic justification; it is nothing more than a jahiliyyah practice cloaked in divine rhetoric. Sadly, the gap between prophetic ethics and modern practice is so wide, expanding by the minute, that it threatens to swallow the very spirit of faith this country was born for. In the case of honor killings and continued justifications of violence against women, women are uniquely robbed of the mercy and fairness that a just system owes them — and that Islam (and by extension, a genuinely Islamic republic) promises them. Even in their death, they are reminded that they are not guaranteed anything in such a country. Their mistake, they are told, is everything they ever did and said before the gun touched their temple, as if life itself was a provocation.

Dare I say: acting in such extreme opposition to the truth of the beloved Prophet’s ﷺ manner and instruction is not only ignorant and unfair, it is far more aligned with what it means to be blasphemous than what so many innocent people are accused of and then killed for. These same men will kill on unproven whispers of blasphemy, yet insult the Prophet's ﷺ legacy themselves, publicly and proudly, with blood-soaked hands, without consequence. So blinded are they by ignorance and misogyny that their violent opposition to the truth of the Prophet’s ﷺ character — cloaked in distorted interpretation and corresponding behavior — is seen not as hypocrisy, but as righteousness. To be clear, nobody should ever be killed over barbaric blasphemy allegations; this is another travesty staining the soul of the country. My point here is to reflect how ironically and ignorantly the tyrants of this nation have distorted what it means to know, love, and protect the truth of the Prophet ﷺ. But that’s the issue: whether through their violence against women and girls or religious minorities, it is clear — they don’t love the Prophet ﷺ. They love themselves and the power their distortions give them.

This is not careless violence. These men do care: about their selfish fantasies masquerading as morality, about their ‘rights’, of which women have no equivalent in their eyes. This is calculated, emboldened by the silence and complicity of too many. That is the core of this crisis. We have among us a population of enablers, operators, and endorsers of this rhetoric. They are self-declared morality police, with eyes trained only to see the ‘crimes’ of women existing, blind to the horrors committed by hands that look like their own. In their so-called defense of Islam, they defile it instead. When they bury girls before their time, so too do they bury their loyalty to the Prophet, and any claim they dare make of honor. The undying tragedy of this country is that the very premise on which it rose from the ashes has been desecrated. What others accuse us of and we fiercely rebut only grows in its prevalence when we afford misogyny more oxygen than we do our girls. For those who stand in a pool of crimson, the shadows of women are more shameful than the spilling of blood, or their betrayal of the man they claim to love.

In the unseen world, though, these women are avenged. They are free to bask in the beautiful blue of God’s flowing rivers of mercy and justice, safe from the tyranny that we are left with. Let it not be the case that we keep sending more women there before their time, through our silence and feigned sorrow. We can not bring back to life Humaira, Sania, Sana, Eman, Noor, Qandeel, and the countless women and girls this cruelty has killed. We can, though, cultivate a culture that rejects such hatred and violence. We can remember that the entitlement, ego, and ignorance that fuel such terror are not eternal, no matter how much they may seem so.

Let us work towards a new day where women in this country [and this world] are afforded the same right to live as men are. How and when that will happen is more a plea to the divine than a question. One rightfully wonders how such a country can get to that point, yet I am no pessimist; I believe realism must always walk hand in hand with prayer, perhaps verging on naivety, but more kindly put, lingering in hope. Hope alone will not suffice, of course. It must be followed by passionate pressure, protest, and policy. Humaira and the countless others like her, those whose names we will never know, deserve more than grief and the occasional article — they deserve justice. Every girl and woman in Pakistan does.

The question is: how much deeper must this river of crimson flow before this country gives women what they have long been owed?

If you are able, consider donating to Legal Aid Society, an organization offering free legal aid to those most in need.

References:

National Human Rights Commission Report on Domestic Violence

Dawn article on Humaira’s death

this was a powerfully written piece. thanks for sharing this..

may Allah bless you for talking about this, powerfully written.