This post is a refined version of an essay I originally wrote as a student of Professor Kazuyo Murata years ago. As this is a subject I regularly return to, this version continues that conversation, offered with hope that it might speak to others wrestling with similar mysteries.

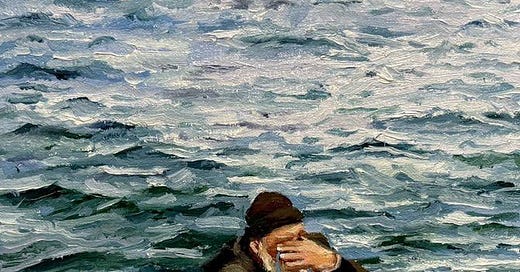

Since humanity's inception, suffering has emerged as its constant companion. Sorrow has a peculiar place in the yarn weaving of every spirit; it twists and turns through and with us, sitting hauntingly beside joy as time ticks us towards our end. As much as we despise it so, it insists on living and lingering, an unwanted guest breathing too loudly for our liking. We pray for its departure, while it has made itself the landlord of a sacred corner deep within us, unmoving and unafraid. This truth begs the question: What do we do with this incessant agony? Shall we force it to wilt through the whims of our mind, or let it bloom and bring with it a new light?

The question of why humans endure pain has captivated philosophers, mystics, and contemplatives across civilizations, generating countless explanations, belief systems, and methods of reconciliation with this fundamental aspect of mortal existence. Among the traditions that have explored this profound relationship between suffering and human experience, Islamic philosophy and Sufism (the mystical dimension of Islam) occupy distinctive positions. Through their emphasis on spiritual devotion and direct communion with the Divine, Sufi saints and scholars have long offered their symphonies as an answer to the questions tugging on our hearts, offering profound insights into the nature of pain and its role in the human journey toward God. Within this rich tradition, the intersection of rational philosophy and mystical insight becomes particularly illuminating when we examine two towering figures: the 9th-century philosopher Al-Kindi and the 13th-century Sufi master Jalaluddin Rumi. Though separated by centuries and approach, both devoted themselves to understanding human anguish, yet their prescriptions for engaging with suffering reveal fascinating divergences. Al-Kindi approached sorrow as a symptom of misplaced attachment—a consequence of clinging to the temporal world rather than surrendering fully to God, arguing that such suffering should be overcome through philosophical detachment and spiritual discipline. Rumi, conversely, embraced a more paradoxical stance: he regarded sorrow not as an obstacle to be eliminated, but as a sacred gift to be welcomed, serving as both divine emanation and transformative force capable of expanding the soul's capacity beyond the limitations of the ego.

In examining these contrasting yet complementary perspectives, we discover how Al-Kindi's philosophical detachment and Rumi's mystical embrace offer divergent yet harmonious paths through the landscape of human suffering—one representing early Islamic rationalism, the other embodying Sufi mysticism, both pointing toward the same ultimate truth.

Suffering in Islam

The fabric of Islamic thought weaves suffering not as an aberration, but as an inevitable thread in the tapestry of human existence. The Qur'anic worldview presents suffering as divinely ordained—a reality that flows from God's will rather than standing in opposition to it. As Watt observes, Islam contains "a high mystical doctrine of suffering," one that positions pain not as a theological problem to be solved, but as a fundamental aspect of the human condition to be understood and navigated.

This acceptance finds its cornerstone in the concept of sabr—patience that transcends mere endurance to become active spiritual resilience. The very emphasis on sabr throughout Islamic teaching implies that life inherently contains trials requiring such steadfastness. To speak of patience presupposes adversity; to cultivate sabr suggests that struggle is not an exception but the rule of mortal existence. Bowker reinforces this understanding, noting that according to the Quran, suffering "is not a theoretical problem but a mere part of life," while Watt extends this by observing that "the Quran assumes that the sufferings experienced by men are caused or permitted by God."

Yet this divine permission of suffering serves a greater architecture of meaning. Human beings, in their fallible nature, inevitably commit acts that distance them from the divine plan. Rouzati explains this through the concept of sharr (evil): "Humankind, through his own volition, acts in certain ways and adapts to specific behaviors that are not per the divine plan; he situates himself in a condition that is referred to as sharr by the Qur'an." This creates a cycle where moral failure breeds suffering, which in turn becomes the crucible for spiritual growth and return to divine alignment.

The nafs—the ego or lower self—emerges as both the source of this spiritual misalignment and the battlefield where suffering wages its transformative work. Islamic thought recognizes that attachment to worldly desires and the fulfillment of egoistic impulses inevitably leads to disappointment and pain, as these temporal satisfactions can never fulfill the soul's deeper longing for the eternal. Thus, suffering becomes both consequence and cure—a divine pedagogy that teaches through experience what revelation instructs through word.

Most importantly, Islamic philosophy maintains that nothing exists without purpose, and suffering too serves the greater design of spiritual evolution. This is what Elshinawy describes as "reason guided by revelation"— the understanding that even pain serves divine wisdom. The Qur'an itself affirms this in Surah At-Tawbah: "Say, 'Never will we be struck except by what Allah has decreed for us; He is our protector.' And upon Allah let the believers rely." Here lies the foundation upon which both Al-Kindi and Rumi build their philosophies, though their architectural choices diverge significantly in how they construct meaning from this shared ground.

Al-Kindi: The Philosophy of Detachment

Al-Kindi approaches the landscape of human sorrow with the precision of a philosopher-physician, diagnosing it as a psychological ailment rooted in misplaced attachment. For this great intellectual architect of early Islamic philosophy, sorrow emerges as "a psychological pain deep within the soul" that manifests through two primary pathways: the loss of cherished things or the failure to obtain desired objects. Yet his analysis cuts deeper than mere description; it reveals the fundamental error in human perception that gives suffering its power over us.

The core of Al-Kindi's logic rests on a distinction between the eternal and the ephemeral, between what belongs to the realm of divine permanence and what exists in the fleeting dance of worldly temporality. He argues that sorrow arises precisely because we anchor our happiness to things that are, by their very nature, transitory. The physical world, with all its apparent solidity and allure, is built upon impermanence—every possession, relationship, and circumstance carries within it the seeds of its own dissolution. To build our emotional foundation upon such shifting sand is to guarantee the earthquake of disappointment.

"Whoever wants what is not natural wants what does not exist," Al-Kindi declares, pointing to the futility of seeking lasting satisfaction from inherently temporary sources. This "unnatural" desire represents a fundamental misunderstanding of reality's architecture. True happiness, he argues, can only derive from sources that share the quality of permanence—namely, intelligence, wisdom, and the connection to God. These eternal truths remain constant regardless of worldly fluctuations, providing a stable foundation for genuine contentment.

Al-Kindi's rationalist approach to sorrow thus becomes one of strategic disentanglement. "We should not choose the permanence of sorrow over the permanence of happiness," he counsels, viewing the persistence of grief as a choice rather than an inevitability. This perspective frames suffering not as a divine gift to be embraced but as a spiritual error to be corrected through proper understanding and deliberate detachment from temporary attachments.

His philosophy aligns closely with Sufism's central call to subdue the nafs, yet his method emphasizes intellectual clarity over emotional engagement with pain. Sorrow, in his view, serves the nafs by keeping us trapped in cycles of attachment and disappointment, preventing us from ascending to the clarity that comes with focusing on eternal truths. Rather than seeing suffering as a necessary stage in spiritual development, Al-Kindi views it as a deviation from our true purpose, a fog that obscures rather than illuminates the path to God.

This intellectual approach to suffering positions Al-Kindi as advocating for what might be called "philosophical therapy" — the cure of sorrow through right understanding rather than lived experience of pain. His method suggests that once we truly comprehend the temporary nature of worldly things and redirect our hopes toward the eternal, sorrow naturally dissolves, leaving space for authentic happiness rooted in divine connection.

Rumi: The Sacred Alchemy of Pain

Where Al-Kindi sees sorrow as a problem to be solved through detachment, Rumi perceives it as a sacred mystery to be embraced through surrender. For the great mystic poet of Konya, suffering transforms from obstacle into pathway, from burden into gift, from wound into the very aperture through which divine light enters the human heart.

Rumi's philosophy recognizes suffering as an essential catalyst in the alchemy of spiritual transformation. As Kaya explains, "Rumi taught that struggle, moods characterized by fear, and other negative feelings are necessary for zuhd, "— zuhd being the turning away from sin and all that distances us from divine love. This perspective reframes struggle not as spiritual failure but as spiritual requirement, positioning pain as an obligatory station on the journey toward our highest potential.

The mystic's understanding rests on a profound recognition: the process of awakening involves a necessary tearing away from the illusions that have comforted us. To detach from worldly attachments—not through intellectual understanding alone, but through the lived experience of loss—requires a kind of sacred violence against the ego's preferences. This ungluing of the soul from its familiar moorings inevitably produces suffering, yet Rumi sees this pain as evidence of genuine spiritual movement rather than spiritual stagnation.

More radically, Rumi positions suffering as a sign of divine presence rather than divine absence. Where conventional thinking might interpret pain as abandonment by God, Rumi's mystical vision perceives it as the very touch of the Beloved. "Suffering is a gift. In it is a hidden mercy," he declares, suggesting that what appears as cruelty from the ego's perspective reveals itself as compassion from the soul's vantage point. This mercy operates through the mechanism of awakening, jolting us from the comfortable sleep of material preoccupation into the uncomfortable but ultimately liberating awareness of our separation from the Divine.

Rouzati illuminates this dimension of Rumi's thought by explaining how the mystic establishes self-knowledge as the cornerstone of spiritual growth. This self-knowledge necessarily includes the painful recognition of our distance from God—a gap that produces genuine spiritual longing. To awaken from the sleep imposed by this world, littered with temptations and unhealthy impermanent attachments, requires the shock of suffering to shatter our complacency.

Rumi's approach demands not merely acceptance of suffering but active embrace of it, maintaining what he calls a "good attitude" toward all forms of affliction. This attitude transformation represents perhaps his most radical teaching: that by connecting both joy and sorrow to the process of reaching God, we participate consciously in our own spiritual evolution. Suffering becomes a form of divine communication, a language through which the Beloved speaks to the beloved soul.

"The longer the duration of hardship, the longer he remains in this state of immanence to God," Rouzati clarifies, revealing how Rumi sees extended suffering not as punishment but as extended intimacy with the Divine. This proximity, though painful to the ego, represents the highest blessing available to the human soul—the chance to remain close to the source of all existence even while wrapped in the flesh of temporal experience.

Comparative Analysis: Two Rivers, One Ocean

The philosophical divergence between Al-Kindi and Rumi illuminates one of the most fundamental questions in spiritual development: Does the path to God require us to transcend suffering or to transform it? Their contrasting approaches reveal not contradiction but complementarity—two streams of wisdom flowing toward the same ocean of divine reunion, each carrying essential nutrients for the soul's nourishment.

The Source of Suffering

Al-Kindi locates the origin of suffering primarily in human error—our misguided attachment to the ephemeral world and our failure to recognize the temporary nature of worldly things. His diagnosis treats sorrow as a symptom of spiritual misunderstanding, suggesting that proper philosophical insight can prevent much of our pain. Suffering, in this framework, represents a deviation from our true nature, a falling away from the wisdom that should naturally orient us toward eternal truths.

Rumi, conversely, sees suffering as divinely orchestrated rather than humanly manufactured. While he acknowledges that our attachments create the conditions for pain, he views the pain itself as God's merciful intervention in our spiritual evolution. Where Al-Kindi sees human failure, Rumi perceives divine pedagogy. This distinction proves crucial: it determines whether we approach our pain with the goal of elimination or integration, whether we see it as an obstacle or opportunity, whether we treat our wounds as problems to be solved or as sacred openings to be explored.

The Response to Suffering

These different origins demand different responses. Al-Kindi's method emphasizes intellectual detachment—using reason and philosophical understanding to dissolve the attachments that create suffering. His approach is preventative medicine for the soul, seeking to eliminate pain by eliminating its causes. The sage who follows Al-Kindi's path cultivates a kind of enlightened indifference, maintaining emotional equilibrium by refusing to invest deeply in temporary things.

Rumi's method, by contrast, calls for emotional and spiritual engagement with suffering. Rather than seeking to prevent or eliminate pain, his path involves diving deeply into it, allowing it to work its transformative magic upon the heart. This approach treats suffering as active rather than passive experience—not something that happens to us but something we participate in consciously, transforming from victim to collaborator in our own spiritual refinement.

The Purpose of Suffering

Perhaps most significantly, the two philosophers diverge in their understanding of suffering's ultimate purpose. Al-Kindi views pain as essentially corrective—it signals that we have wandered from the proper path and need to redirect our attention toward eternal truths. Once this correction occurs, suffering becomes unnecessary, having served its function of returning us to the right understanding.

Rumi envisions suffering as transformative rather than merely corrective. Pain doesn't simply signal error; it actively reconstructs the soul, breaking down the barriers between human and divine consciousness. In this view, suffering remains valuable even after we achieve spiritual understanding, continuing to deepen our capacity for divine love and refine our spiritual sensitivity.

The End Goal

Both philosophers ultimately seek the same destination: union with the Divine and liberation from the ego's tyrannical demands. Yet their different routes suggest different understandings of what this union entails. Al-Kindi's path emphasizes the transcendence of human limitation through philosophical clarity, rising above the emotional turbulence that characterizes unenlightened existence. His ideal represents a kind of spiritual sovereignty, where the soul achieves independence from worldly circumstances.

Rumi's path points toward the transformation rather than the transcendence of human experience. His ideal involves not rising above feeling but allowing feeling to become a vehicle for divine encounter. Where Al-Kindi seeks independence from suffering, Rumi seeks interdependence with it, recognizing pain as a thread in the larger tapestry of divine love. While his sacred alchemy of pain offers a profound reframe, its demands on the soul to see mercy in agony can understandably feel unreachable for those caught in suffering’s sharpest throes. Nevertheless, there is a liberation he promises we can experience, if only we allow ourselves to see that far.

This fundamental difference reveals a profound insight about the nature of spiritual development itself: perhaps the journey to God requires both the clarity that comes from detachment and the depth that comes from engagement, both the wisdom that transcends suffering and the love that transforms it. In our contemporary era of perpetual darkness, with seemingly endless sources of pain ready to wound us at every corner, we are constantly confronted with the knowledge that suffering exists as our birthright, a promise of what it is to be human. Perhaps the solution lies in the idea that we need both Al-Kindi's philosophical medicine and Rumi's mystical alchemy: the ability to step back from unnecessary attachments while simultaneously opening our hearts to the sacred dimensions of unavoidable suffering.

Ultimately, they may take different routes, but both men meet in the same garden. They, like the rest of us, embark on a journey to one vision – transcendence to a higher good. How that is sought may be via discipling one's mind or breaking open one's heart, but every soul shall reconnect to the ultimate source eventually. Perhaps we ought to consider that union shall arrive through the undying companion we so desperately seek to avoid.

In closing, we must remember that suffering transcends the realm of philosophical inquiry—it dwells in the sacred territory of lived human experience. While Al-Kindi's rational approach offers valuable wisdom, the full truth of sorrow cannot be contained within intellectual frameworks alone. The most luminous example of this lies in the life of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, whose existence was interwoven with profound grief yet radiated divine light. He who was closest to God experienced the deepest sorrows—the "Year of Sorrow" that claimed his beloved Khadijah, the countless tears he shed throughout his prophetic mission, the weight of witnessing humanity's struggles. His sorrow was not evidence of spiritual failure or worldly attachment, but rather the natural expression of a heart so expanded by divine love that it could hold both the joy of God's presence and the pain of creation's longing.

The Prophet's ﷺ tears were not shameful weakness but sacred testimony to the depth of prophetic compassion. Through his example, we understand that sorrow is not a theological problem requiring a solution but a fundamental thread in the fabric of human consciousness—one that even the most perfected soul cannot escape, nor should seek to. His grief sanctifies our own, reminding us that to feel deeply is not to fall short of divine expectation but to participate fully in the human experience that God, in His infinite wisdom, has ordained for us. In His everlasting grace, He has woven our souls with threads of joy and sorrow alike. He knows the pain we can not speak of, can not comprehend. He does not berate us for feeling such; on the contrary, he echoes the beautiful truth of His mercy throughout His Word. This is promised to humanity in Surah Ash-Sharh with profound simplicity and tenderness:

This is not merely consolation, but a cosmic truth that our struggles carry within them the seeds of their own transcendence, and that every wound becomes a gateway for divine grace to enter. That ease is the point we all spend our lives reaching for, knowingly or not. It is the tranquil destination we reach after bloodying our feet. So let us look at our sorrow with this grace; after all, the wound is where the light enters. In acknowledging this, we honor both the tears of prophets and the sacred sorrow that shapes every seeking soul.

References

Aslan, A., 2001. The fall and the overcoming of evil and suffering in Islam. A Discourse of the World Religions, 2, pp. 24–47.

Bowker, J., 1969. The problem of suffering in the Qur'an. Religious Studies, 4(2), pp. 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034412500006132

Elshinawy, M., 2018. Why do people suffer? God's existence & the problem of evil. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research. Available at: https://yaqeeninstitute.org/read/paper/why-do-people-suffer-gods-existence-and-the-problem-of-evil.

Jayyusi-Lehn, G., 2002. The epistle of Ya'qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi on the device for dispelling sorrows. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 29(2), pp. 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/1353019022000045887

Kaya, C., 2016. Rumi from the viewpoint of spiritual psychology and counseling. Spiritual Psychology and Counseling, 1(1), pp. 81–104. https://doi.org/10.12738/spc.2016.1.0005

Kennedy-Day, K., 2020. Al-Kindi, Abu Yusuf Yaqub Ibn Ishaq (d.). Muslim Philosophy. Available at: http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/ip/kin.htm.

al-Kindī & Ivry, A.L., 1974. Al-Kindī's metaphysics. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Rouzati, N., 2018. Evil and human suffering in Islamic thought—towards a mystical theodicy. Religions, 9(2), p. 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9020047

Rustom, M., 2010. Rumi's metaphysics of the heart. Mawlana Rumi Review, 1(1), pp. 69–79. Available at: https://www.mohammedrustom.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Rumis-Metaphysics-of-the-Heart-MRR-1-2010.pdf

Watt, W.M., 1979. Suffering in Sunnite Islam. Studia Islamica, (50), pp. 5–19. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1595556

Hey Zahra,

Thank you so much for writing this masterpiece and putting it all together. Words aren’t enough to express my appreciation for your effort. May your heart be filled with happiness, and your mind enriched with knowledge.

I loved reading this as it was a beautifully researched and eloquently written piece. I deeply appreciate the effort and the rich exploration of various philosophical viewpoints. The weaving of historical insight, theological reflection, and lived human experience made it a truly compelling read.

That said, sometimes I wonder whether all these philosophers have made this issue more complex than necessary. Perhaps the framing of this can be simpler than what has been made of it. The Quran already provides a direct lens - “Whatever befalls you of hardship - it is because of what your own hands have earned. But He pardons much” (Surah Ash-Shura 42:30). Al-Kindi’s view seems to be in alignment with Allah’s (God's) message here and that is that pain in such cases is a divine correction, and not an automatic gift. The Quran also reminds believers, “If you are suffering, they (the non-believers) are suffering as you are suffering - but you hope from Allah what they do not hope” (Surah An-Nisa 4:104). Suffering therefore is not sacred. What transforms it is one’s orientation to God.

Even more directly, Allah tells us, “We did not wrong them, but they wronged themselves” (Surah An-Nahl 16:118). This places responsibility not on fate or divine favoritism, but on the moral compass we follow or ignore.

What Al-Kindi said therefore aligns more closely with this: that pain corrects our direction. We’ve seen companions like Bilal endure excruciating torment and yet rise spiritually through sheer submission, not intellectual frameworks. Others faltered under pressure, and the Prophet (may the peace and Allah’s blessings be upon him) made space for that too - he understood the human threshold.

The bottom line is that we learn from the Quran that submission and love for Allah place us in a state where suffering is reframed. It is softened by submission, conviction and fortified by hope in the divine. While parts of one’s pain and suffering may serve as a test of faith, the Quran also shows that much of it can be avoided by staying on the straight path.

Let’s not forget what the Prophet (may the peace and Allah’s blessings be upon him) did or advised us in the state of sorrow - he invoked God, he made dua (supplication) - he did not indulge in abstraction or philosophical theorizing. As you rightly say in your article, sorrow dwells in the sacred territory of lived human experience. In fact, he taught numerous specific supplications for sadness, distress, and fear. And we must ask: what is the purpose of these duas, if not to gently teach us that sorrow isn’t to be endlessly analyzed, but to be lifted, surrendered, and healed in the presence of the One who knows us better than we know ourselves?

Thank you again!