A Poem Never Dies

On Words as Memory, Mercy, and Resistance

I place a necklace of poetry

around the neck of the moment,

and flee the limitations of time.

— Hanane Aad, The Tools of Patience

(Translated by Aad and John Wilmot)

It was around midnight, an early August evening, 2018. I was about to close my laptop and surrender to sleep when something caught my eye. I was mindlessly scrolling Facebook, for God knows what reason, when I noticed the word URGENT illuminate my blue-lit screen.

Curious, I skimmed the post, reading a plea from a grad student for someone to step in as president of the King’s College London Poetry Society before the deadline, for otherwise, it would cease to exist. Seeping through the screen before me was a sadness so thoroughly present in the poster’s tone that, without thinking, I messaged her after barely a moment’s deliberation.

I now consider that perhaps it was not so sudden after all.

My great-grandfather was a barrister who despised the fact. Despite the years of study that carried him across blue seas and skies to London and Lincoln’s Inn, he spent his days not in the courtroom, but in the company of his true beloved, a book. In the 1920s, his haveli was renowned for its dinner parties — night after night, he welcomed a dozen souls, many a time people he had never met before, drawn from every class and creed to enjoy an evening of fine food, discussion, and of course, poetry. Among his guests often sat his close friend and legendary poet, Muhammad (‘Allama’) Iqbal.

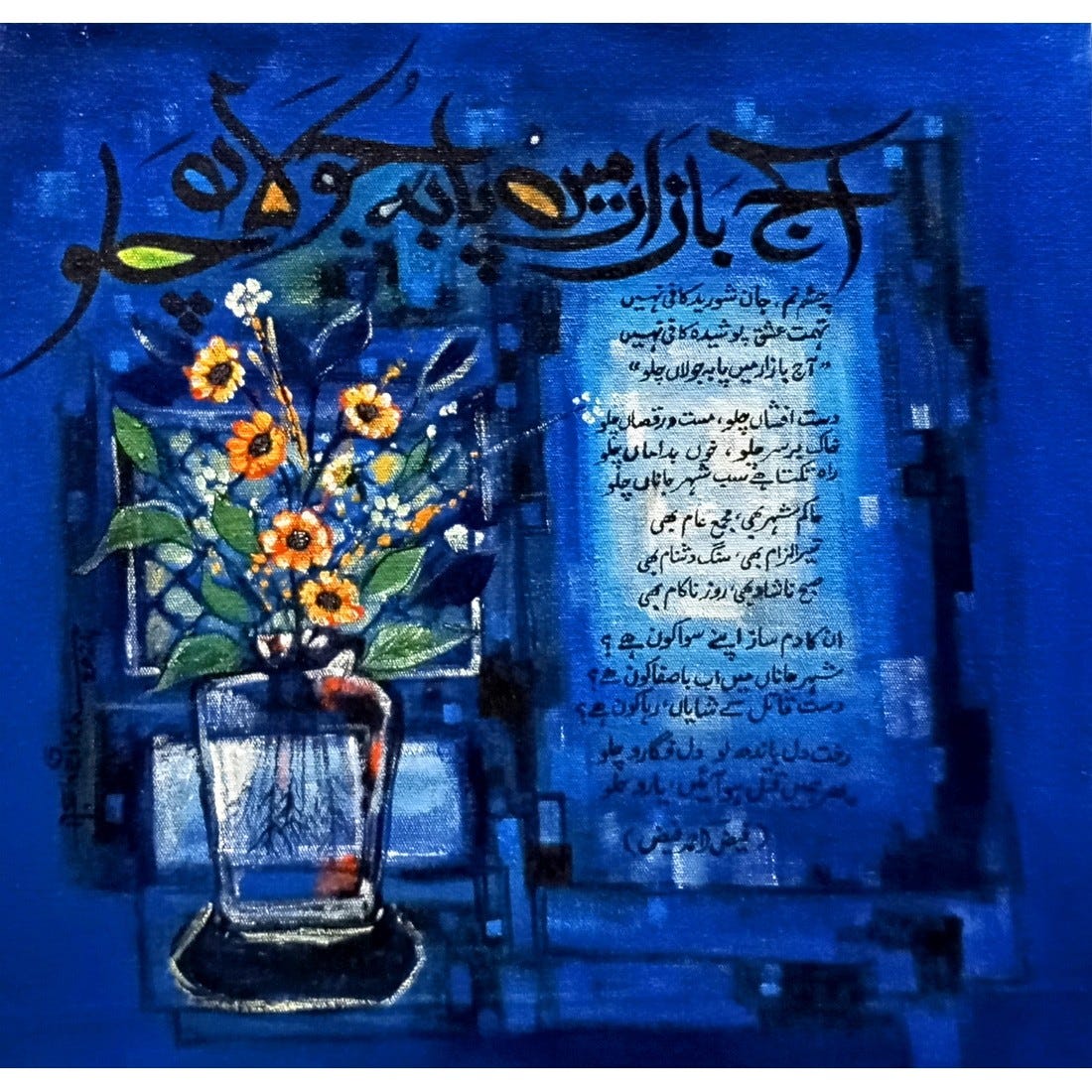

It is a profound sorrow that post-partition, the depression invoked by the loss of his home meant he spent most of his days in silence. What could never die, though, was his love of a poem. Poetry was an inheritance grief could not erase, for it lives beyond border, belief, and time. His son, my beloved grandfather, breathed poetry as though it were oxygen. He carried it in memory and on his tongue, in Persian and Urdu, in verses he recited with a tenderness so deep people often asked to hear him recite. His house was adorned with it, stanzas etched into walls and woven into air. For my mother, who grew up beneath his voice, poetry was akin to scripture, holy in its timelessness and reverence. Poetry followed her throughout her life, even shaping it; she and my father met in a bookshop while reaching for the same book, Kahlil Gibran’s Mirrors of the Soul.

In my own life, it has served as a tool for me to connect with myself, my family, my faith, and every aspect of my existence that fails to find solace in the material. In university, as a part of my society events, I used to host weekly poetry readings. One evening, there were only a handful of us, including a Portuguese student who only wrote in his mother tongue. When it was his turn, none of us understood a word, but we listened anyway. His poem was long, steady, without pause. He offered no translation, but it was beautiful nonetheless; I found myself listening as attentively as I would had I understood the language, almost straining myself, leaning forward slightly, as if to catch what I felt it was giving. We applauded when he finished, and he smiled shyly. I still think of that evening fondly; such is the power of a poem: to move beyond comprehension, to speak to the soul even when the mind cannot follow.

Perhaps its sweetest power is that poetry has ever so generously shared its sacred reality across traditions; it lives universally and eternally as people’s power, prayer, and persistence. It transcends language and the limits of the material to ever so softly usher us into a higher realm of feeling, of being. A gentle transition from the physical to the spiritual, from the outer world to the most hidden chambers of the heart. In these truths alone it is sanctified as a mercy.

From the very beginning, poetry has held a special place in the Islamic tradition. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ loved the poets who placed their verse in the service of truth, reminding us that a single line of poetry could pierce like an arrow, defending the oppressed and glorifying God. Words were thus always held in the highest regard, holding the truth that they have never been mere ornament, but witness, weapon, and worship. The Sufis have carried on this legacy best. When the heart yearns for the Divine, when intellect fails to name the unnameable, only poetry can carry the weight of that longing — a weight they have masterfully carried time and again. Whether Rumi or Hafez, Bulleh Shah or Shah Abdul Latif, in whatever tongue and time, they each transformed verse into a ladder of ascent. Recited, sung, whirled to, their words transformed the act of reading into a new level of living. In them, the boundaries of language collapsed: Persian, Arabic, Punjabi, Sindhi, Turkish, Urdu — all became vessels of the same ocean. To this day, their poems echo in qawwali gatherings, in folk songs, in whispers of zikr, reminding us that poetry can be prayer, and that beauty is a path to God.

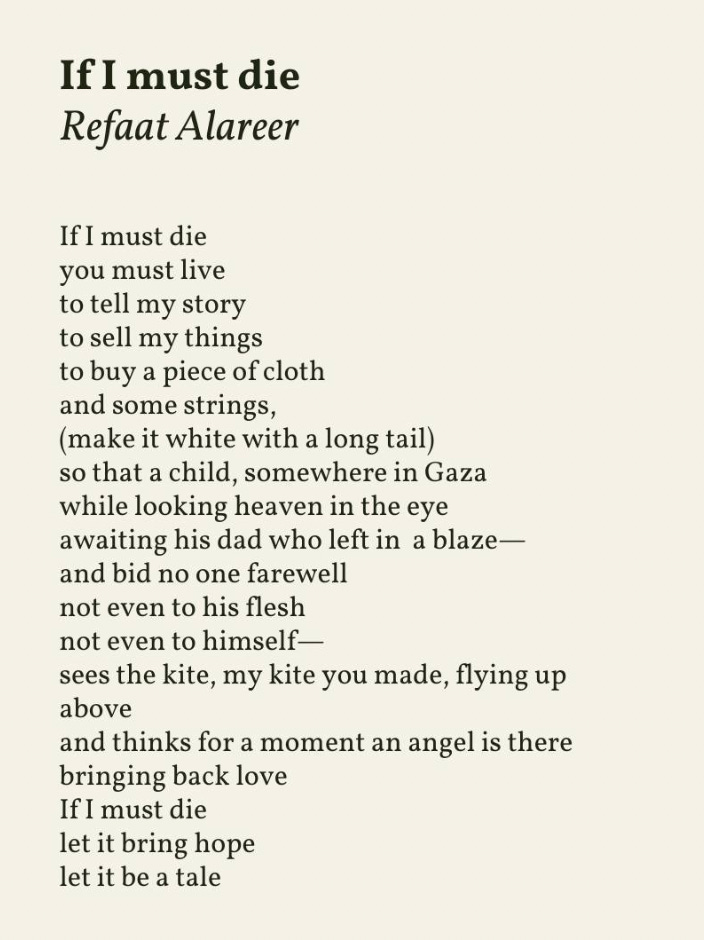

Just as it functions as a balm, so too does poetry as a blade in the hands of the oppressed. When tyrants rose, poets have sharpened their pens into swords. In Pakistan in the eighties, Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge became a revolutionary anthem, so feared by the military dictatorship that it was banned — yet still sung, still remembered. Even now, forty years later, amidst the country’s endless political turmoil, people return to those lines as a comfort, and a reminder, that justice shall prevail. Today, who better an example of this than Refaat Alareer, the Palestinian poet-martyr who, before being killed by the genocidal entity who feared his pen so deeply, left us his final words:

His life was taken, his home destroyed, but his poem remains — carried in the mouths of millions, in marches and vigils, in whispered prayers. His voice continues, because poetry refuses the silence that tyrants set the Earth on fire for.

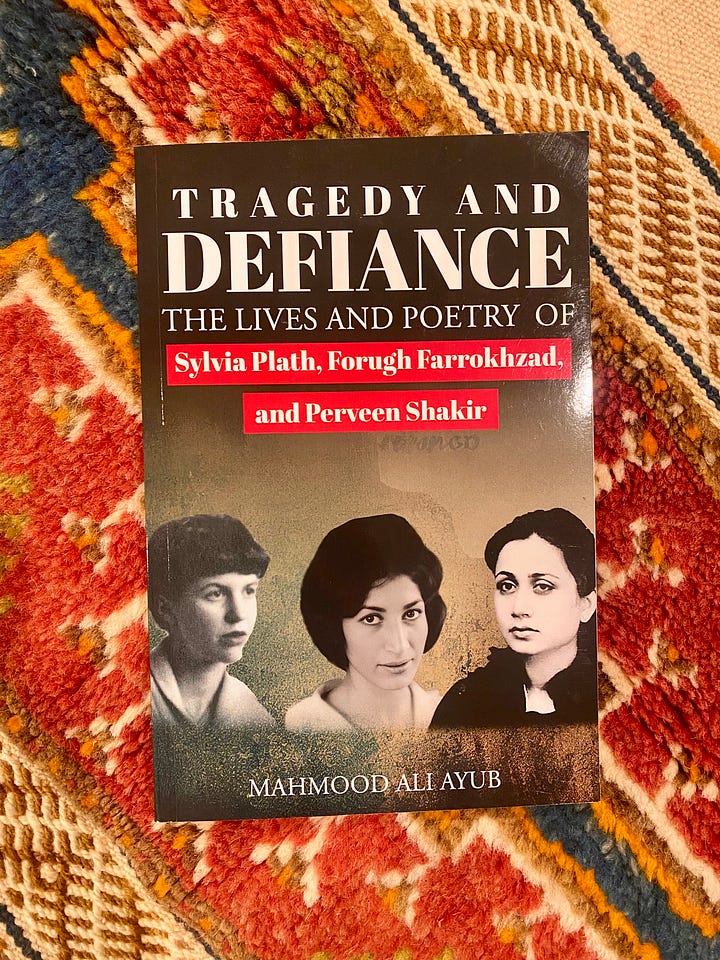

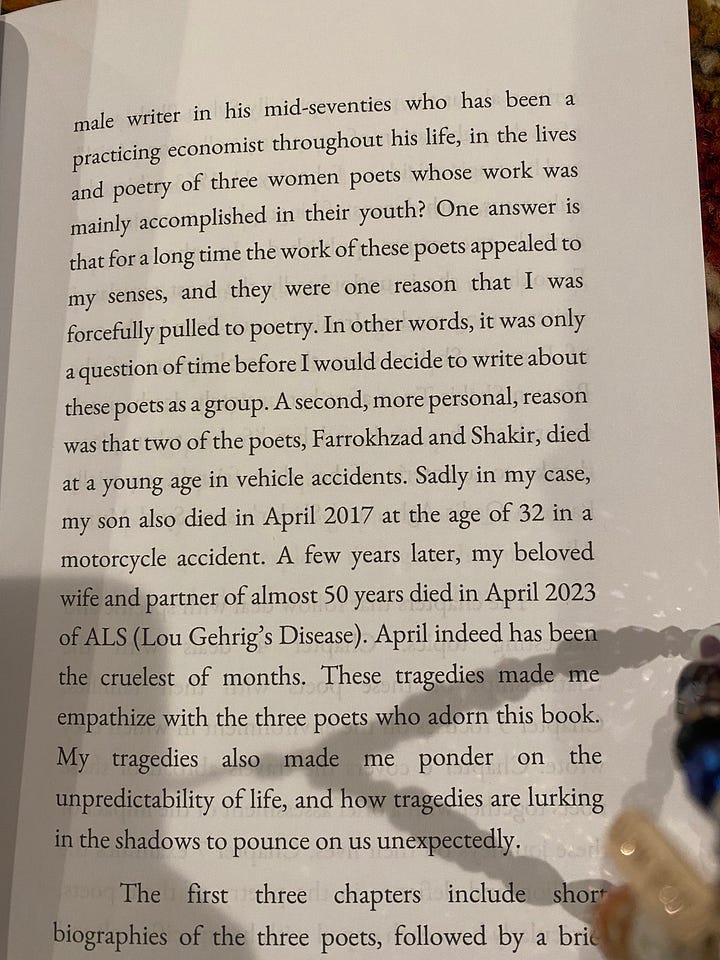

This power to resist tyranny is mirrored in the struggle against a more intimate silence, a truth I was reminded of while reorganizing my home library recently. While doing so, I came across a book written and gifted by a family friend, which caught my eye immediately with its title: Tragedy and Defiance: The Lives and Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Forugh Farrokhzad, and Parveen Shakir. Even just reading the introduction, I was reminded at once of how poetry for women throughout history has been a tool of resistance, not only against rulers, but against silence itself.

If you read the excerpt shared above, you’ll see how the writer so beautifully captures the true power poets wield: to bring people together, heart to heart, no matter how much time or difference separates them. They become healers, muses, guides, and in that way, somewhat akin to saints.

Thousands of miles away, I have felt the energy of such saints, just as I have felt the echoes of this inheritance live on in the corners of my American life. The walls of my local mosque, for instance, are beautifully adorned with Persian poetry. In my parent’s house, it’s tradition to host regular gatherings that always begin and end the same way: with the recitation of a poem. Verse remains the opening act of any event, the blessing that sanctifies the evening before food or music or laughter. Sometimes, one verse isn’t enough, and friends and family alike go on and on, until time no longer seems real, blurred in the blissful haze of a poem's breath.

What else could play this role? Poetry weaves beauty into the fabric of our lives. It infuses faith with feeling, culture with depth, and ordinary evenings with eternity. It is both fragile as a breath and enduring as scripture. It is a mercy, and when nothing else remains, it is what remains.

Some of my fondest memories to this day are those of my little adventures with that university poetry society; I think of the friends it gifted me, the journeys I made and the journeys that made me. I think back to that evening in August 2018, to the many that followed, and to the countless nights that led up to it — nights my great-grandfather also spent in the touch of London’s moonlight, in the peace of a poem. A lineage carried not only by blood but by verse, stretching across continents and centuries, from Delhi to London to Islamabad to Washington. From Hafez to Ghalib to Iqbal to Faiz; from Pessoa to Rilke to Oliver to Glück. Sometimes I come across a verse by any one of these greats and feel closer to them than anyone. Depending on my day, mood, and phase of life, the same can be said about so many beloved writers whose pen I praise God for allowing me to know.

A poem lingers in the silence after its recitation, in the rhythm of breath that once carried it, in the memories of those who once were and the promise of those who will one day be. A poem slips past the limits of body, of border, of time. It outlives homes lost to partition, voices swallowed by exile, and even the poets themselves. It is our prayer and protest, memory and mercy. It is a way of saying what cannot be said, of holding on when everything else is falling away. And so when I read, write, or listen to a stranger recite in a language I do not know, I feel the continuity of that truth. The certainty that as long as we breathe, ache, and be — that which will rise to meet us is that which shall never die — a poem.

You may enjoy:

the perfect post for me to become a subscriber heh.

loved the part about the Portuguese poet. i feel a sense of...detachment, or missing out, in that my skill in the most poetic languages is too little to truly enjoy most of the poetry (arabic and urdu). still, i'm grateful for however much i do understand, for i have my foot through the door, and i'd much rather understand even half a couplet than to not understand at all.

on the topic of urdu poets, i had the most bizarre and serendipitous meeting with an urdu poet in the subway of toronto. he claims to be the sole student of the famous Jaun Elia, having lived with him for over a decade (iirc).

he spent a long time writing his first collection, then somehow ended up meeting Jaun, and long story short, Jaun told him to rip his manuscript and toss it in the bin in front of him if he (Qaisar, the poet i met) wanted to become a real poet and learn from Jaun. And he did just that.

i wrote more about this encounter in one of my first posts, if you're curious to read more.

Truly, truly moving! Your storytelling keeps your voice alive in the hearts of your readers.